Last week I wrote a bit about why Spinoza was interested in interpretation of the Bible — in a nutshell, the better we do it, the harder it is for people to abuse Scripture to their own ends.

We see them advancing false notions of their own as the word of God and seeking to use the influence of religion to compel other people to agree with them.1

What does doing it well involve? The main thing, in Spinoza’s view—the thing from which everything else follows—is to honor the fact that it was written by people who are not us. That it is, as one scholar put it so beautifully, “part of the givenness of a world we did not make.”2 Whatever we do when we read Scripture, we are accountable to this.

So count me gobsmacked to find the following sentence in a recent essay by a prominent biblical scholar:

We’ve got the author of the text already — the author is us.3

What the author of this sentence means is that we cannot know the identities of the people who wrote the texts in the Bible. The idea of intellectual property did not exist in antiquity, and texts did not have copyright pages or (with very rare exceptions) author signatures. In fact, when a text is attributed to someone like Isaiah or David or Moses, this meant something quite different in antiquity. (If you want to get a handle on how that worked, read this.) So, if we can’t know their identities in any direct way, anything we can know about them must be based on our interpretation of the text they wrote. Our sense of the text’s authors will indeed evolve as our interpretation of the text does. So it is accurate to say that our understanding of the authors has something to do with us.

But saying that we are the authors is next level. And that’s worth our attention because it is both wrong and dangerous.

It is wrong because it reduces interpretation to something that depends solely on readers. You might say it collapses the author into the reader. It is true that we aren’t just passive recipients of meaning when we read. We play an active role in creating it. We all come to the text with different experiences, interests, and assumptions. We see different things in it. And this has been true across the history of biblical interpretation, which is why it is so rich and diverse and fun to read about. But we don’t get to make it up. There are words on the page to which we are accountable. They create possibilities for what the text can mean, but they also place constraints on it.

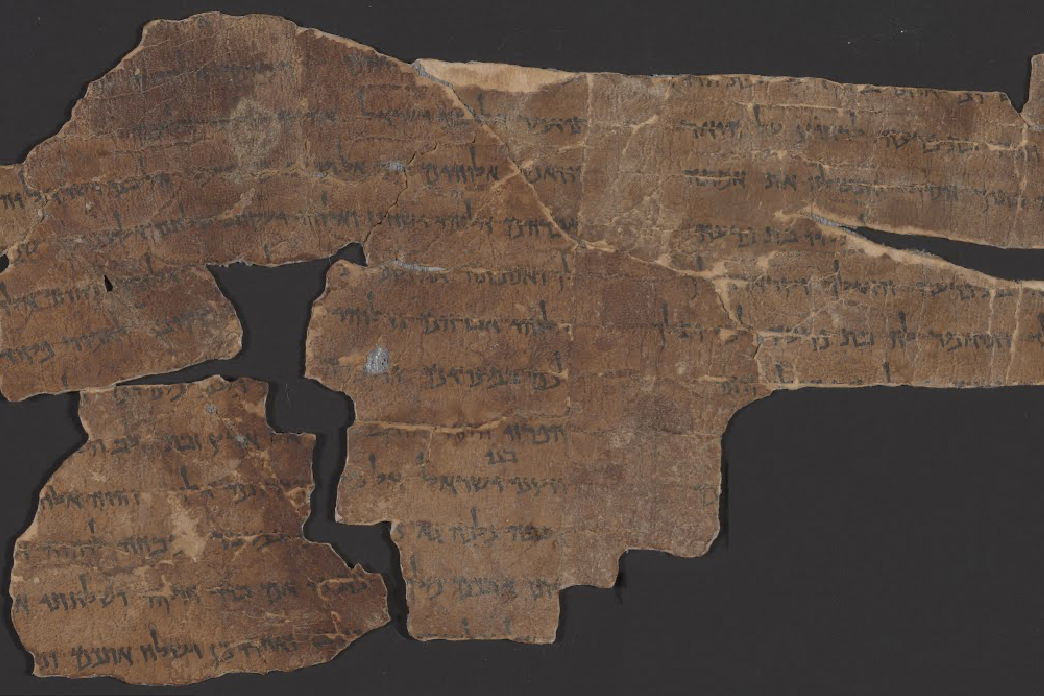

Those words to which we are accountable were written by people who are not us. Even if we cannot recover their identities, we know that they lived in a time and place very different from our own, politically, economically, and culturally. They wrote in languages we do not speak, on media that are foreign to our computer-based modes of writing. This shows in the texts—it shaped their message and how they crafted it. Sometimes the ways in which the text is grounded in the past proves quite relevant for what it might mean to us even today. (I wrote about one such case here.)

The groundedness of the text in a world we did not make is not easy to get a handle on. In fact, it is very difficult. Our job as biblical scholars is to help. It is tempting (even for us) to say “Why bother?” But herein lies the danger. When we stop grappling with the fact that the possibilities for and constraints on meaning were created by people who are not us, it is easy to (falsely) see ourselves as the authors.

But once the author is us, there is nothing to prevent the circumstances that prompted Spinoza to revolutionize study of the Bible in the first place.

- Benedict de Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise, edited by Jonathan Israel, translated by Michael Silverthorne and Jonathan Israel, Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2007). ↩︎

- John Barton, The Nature of Biblical Criticism (Westminster John Knox, 2007). ↩︎

- Joel S. Baden, “Sources without Authors,” in The Literary History of the Pentateuch: Collected Essays (Mohr Siebeck, 2025). ↩︎